“Nobody knows anything... Not one person in the entire motion picture field knows for a certainty what’s going to work. Every time out it’s a guess and, if you’re lucky, an educated one.” - William Goldman, Adventures in the Screen Trade

With this single, famous quote William Goldman—author and screenwriter of The Princess Bride, Marathon Man, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, along with countless others—outed The Emperors of Hollywoodland as wearing no clothes. Most creative Gatekeepers don’t ‘know’ what they’re doing, or why. The industry is run by gut feelings, instinct, and luck… not by plan.

Casablanca was a huge hit.

It’s a Wonderful Life was a flop.

You can’t guarantee a hit. If you could, Hollywoodland would be a hit machine, instead of a simple story factory. Terrible projects become massive successes. Amazing films go into the dustbin. But because of the investment involved the money-crunchers always try to guarantee hits, or at least stack the odds in their favor. It’s an unwritten part of their job description.

I’ve been in meetings where the executives involved disparaged a show that was about to open on the coming weekend, speaking confidently about what ‘crap’ it was, and how it would be the biggest bomb their company had produced, only to find it topping all box office charts days later. In a meeting the following Monday those same executives would discuss with pride how they knew all along it would be a huge hit, and they were adjusting their buying accordingly. They wanted more of what they had always known was an ‘obvious’ success.

As if I’d somehow forgotten the conversation we’d had just days earlier.

The people with these shifting perspectives are usually the Gatekeepers you must charm in order to enter the magic kingdoms of Development and Production.

One of my more memorable meetings came during a science fiction boom in movies and TV. I met with a Gatekeeper who had acquired the rights to Conan The Barbarian, and he knew exactly what the fans were looking for. In an office bigger than my apartment he said to me with absolute certainty, “You know what would make Conan great? Picture this: Conan—in space.” I laughed, until I realized he was completely serious.

The meeting was over. I didn’t get the job. Gate kept.

What I began to realize about the TV and movie business is that the executive position is largely filled with fans of the medium, all with strong opinions about what makes a success—would make more success—with little or no training in story, writing, editing, or visual storytelling. They had full faith and confidence in their own instincts (usually centered around some buzzword or other), while simultaneously living in perpetual fear of losing their jobs. Because—as I’m sure they heard often… as I myself was occasionally told—“I can find three people to replace you tomorrow.”

The flip side of this uneasy equation is that most Creative Types are generally artists who need money to achieve their goals, but are terrible at things like math. Schedules. Budgets. Talking to other human beings. So they live in an awkward symbiosis with executives who handle those ‘unpleasant’ tasks. If one or the other side of these opposing poles of the magnet shifts its balance, the bullet train very quickly seizes the tracks, or worse… goes flying off the rails.

Because the motivation of Gatekeepers is different than the motivation of artists, Creative Types and Gatekeepers are often at balance-shifting odds. It’s more than just a difference in point of view between ‘greedy money people’ and ‘oblivious artists,’ what’s commercial, versus what isn’t. It’s a difference in point of view about things like what’s most important in a show; Story, Character, Theme, Tone, Arcs, Audience Desire, Market Demands, Talent, Casting, Previous Success, and on and on. It’s not the money, or the need for it that goes off-balance. It’s the divergent goals. As one Creative Type once told me, “I’m not here to give the fans what they want. I’m here to give them what they need.” Which—I think—said more about that Creative Types needs than the needs of his project. His Gatekeeper, conversely, preferred the Creative Type give the fans what they wanted. When fans didn’t respond to ‘what they needed’, the executive replaced said creator.

Gatekeepers need success. Creative Types need adoration. Fans need what they want. Creators want what they need. Both think they have the secret sauce.

Nobody knows anything.

In 1999 I left animation and went to work in comics. I was a little stunned to find that the process, and the attitude, were basically the same.

Most editors (Gatekeepers) were fans of the material. They had very strong opinions about what their audience wanted.

The big difference in comics was that they knew their fanbase better than I did. I could get deep into explaining the closed feedback loop that comics publishing has become, and why; how the market for comics is now by fans, for fans… exclusively; but it’s become rather obvious, and something those fans are rather proud of, and don’t want to change.

But I was writing my comics for a general audience (which is what my boss, Bill Jemas had asked for), and a general audience was never going to drive out of their way to come into a comic shop. Meanwhile the fans wanted something else. Needed something else. The fans had become the exclusive (Direct) market, and I couldn’t write for them. I tried, at points, and it was a mistake. I needed to write something other than “HULK BATTLES THE ABOMINATION… AGAIN!”

No harm, no foul. You can’t fight reality. Don’t dirty someone else’s pool.

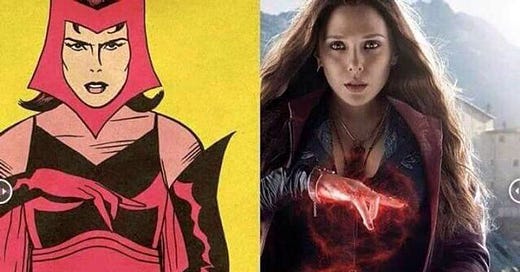

So I came back to Hollywoodland, and the parallels only became more clear, more obvious, especially once Marvel Movies took over the world. They became a huge success, mostly because the fans running the operation translated the biggest name hits from the comics for a General Audience. Which is what you need when you’re introducing new characters to a fresh market, and starting with origin stories. But as the movies and TV series’ progressed, an unfortunate reality set in. And it was the opposite of working in the closed loop of the comics market. They shifted the movies toward fandom looking to develop a large, and devoted audience.

In-jokes. Easter Eggs. A focus on big action. A focus on returning villains. The Blip and it’s repercussions. Alternate dimensions and outer space adventures where the specialness of superheroes is less… special. Loss of vulnerability. Loss of personal growth arcs. And worst of all, the dreaded multi-headed monster in every Marvel superhero room…

… continuity.

Fans love continuity.

General audiences are confused by it.

Fans are devoted.

General Audiences are fickle.

Fans want ‘old’ in the trappings of the new.

General audiences ‘new’ in the trappings of the old.

General audiences aren’t all fans, and don’t respond to the material the way fans do. They don’t complain and threaten creators when a comic or movie or TV series isn’t to their liking. They quietly vote with their feet. They also rarely get online and praise what they’ve discovered. They read, or watch, what they enjoy, then turn to something else they can read, or watch, and enjoy.

Fans hate-watch, then get online to complain that the show or movie failed because it wasn’t close enough to the comic book source material. So fan-based numbers don’t change a lot in the short-term. They do eventually vote with their feet as well, when the entertainment level they seek drops far enough, leaving only the most devoted, vocal, and intense fans. For you chefs out there, focusing on fans alone is like making a reduction, cooking the sauce on a low heat until the remaining flavors are thickened and concentrated. Reduce too far, and you’re left with something dark, and sticky, that no one wants to eat.

General audiences are the first to boil out of a simmering reduction. They just change the channel and say to whoever else is in the room, “Enh. Boring. Wanna watch something else?” Recently the people running Marvel have boiled away their general audiences in a desire to ‘make their general audience into fans,’ while at the same time changing movies and TV shows far enough from the source material that the comics fans are dissatisfied.

So the Marvel Studios approach has now turned most everyone away. Largely because there is no middle ground. You can serve one audience, or the other. Not both.

It’s a little known fact, but when I was writing Uncanny X-Men my sales were almost the same as Grant Morrison’s on New X-Men. But the ‘common knowledge’ among fandom was that Grant was selling a metric tonne more than me. Consequently many fans complained that they wanted more stories like Grant’s, and many did quit my version of the book.

But at the same time I brought back a lot of old readers who had given up on the X-Men, as well new readers who had never read about a mutant in their lives. Mark Millar once told me at a convention—very kindly—that my X-Men was the only comic in his monthly box of Marvel freebies that his wife would read. Unfortunately, even with winning her over—in the end, numbers-wise—my run was a wash. My numbers stayed close to Grant’s… only a few hundred less. Neither of us clearly outdistanced the other, and no one was building an audience larger than what had been attained on the last successful run that preceded us, other than brief sales-spikes. Certainly not to the numbers that Jim Shooter oversaw with a company-wide edict about making sure every Marvel Comic was accessible to every potential new, general audience reader buying a comic for the first time. See that box that used to be at the top of every splash page? Spider-Man’s expository internal monologue? That’s not there for the long-term fans.

So why is the fan-direct approach a problem for casual viewers? Not making every movie entirely accessible to a first-time audience member? Well, I used to write a lot of the Marvel characters, had read them throughout my (much) younger life—yes, I was a fan—and even I had a hard time following Marvel Studios continuity. I don’t watch their movies with the same attention to detail that I muster for something like… say…. Casablanca.

“What was The Blip, again? Oh. So this isn’t ‘our’ world anymore, it’s an alternate dimension where half the world died and came back, and everyone’s whining about it? And when did Scarlet Witch become evil? Oh, she went crazy because… what happened? She fell in love with Vision? When? Did we ever see that? Oh, my God, the chemistry between Chris Evans, and Scarlett Johansen is off-the-charts intense! Studio heads sleep on their knees praying for that kind of chemistry, and… hold on… what? She’s in love with The Hulk?”

(Sigh)

Nobody knows anything.

In its heyday, Marvel’s biggest comic book hits sold millions of copies. My run in the earl 2000’s sold about 127,000. Now they sell thousands—or worse—hundreds.

Can a larger audience be reached? At one point Louise Simonson and I discussed creating a girls romance comic to reach a new market. Gatekeepers said, “No. Women don’t read comics.” Then manga struck like lightning, and I watched women walk up to bookstore cash registers with armloads of the things. At ten bucks a pop.

Nobody knows anything.

“The days of million sellers are gone,” A Gatekeeper recently told me.

WebToons routinely sells multiple millions of various digital comics.

Nobody knows anything.

So am I complaining? Where am I going with all this? Am I anti-fan? Anti-comics? Anti-Studio? Anti-continuity? Anti-executive?

No. I am a fan. I’ve been an integral part of varying studios. Heavily into continuity (don’t get me started on Star Trek). What I’m saying is; know and understand your audience, and accept the limitations of that audience. Or revel in the breadth of an audience that you may not yet be fully aware of. Then accept that what you create may not become the biggest weekend blockbuster in modern history, but you’re doing what you love, connecting to like-minded souls, and paying the bills. If you serve your audience—particularly an audience that feels underserved—you may find a niche for yourself that allows you the freedom to do what you love every day.

When I was a young, freelance illustrator, there was a metaphoric quote going around about knowing your audience even then. It went:

“You can’t sell pictures of naked men to Playboy.”

The days of the Gatekeepers are gone. Your reach is unlimited. Small, local audiences can now be discovered, and connected—globally.

Crowdfunding, digital delivery, a computer or multiple computers in every home, in the palm of every hand, all mean you are now your own gatekeeper, and your reach is worldwide. In the past, comics sales, movie and television viewership, were all controlled by Gatekeepers. Studios. Networks. Publishers. Editors. Executives. Printers. Distributors. Store owners. Everyone had a say in the audience you were allowed to reach.

Now you can connect easily to that one manga fan in Marfa, Texas. Or maybe you get incredibly lucky and create the next Twilight, or Fifty Shades of Gray, or Harry Potter, or whatever other project no Gatekeeper would touch that then made millions and reached a worldwide, General Audience.

You want to make a superhero movie? Make one! But know your market, and accept the limitations of potential low-budget special effects, and costuming. Every superhero creator wants to be The Russo Brothers, or Jon Favreau, but that’s more about a need for an ego-boost, and less about reaching your audience. People print up super expensive European album-type hardback books because they love seeing their work printed in them—but their fans can’t afford to buy them. Couldn’t you be happy paying the bills while making what you love?

You want to make a Western comic? Great! But if it has to be in print—in pamphlet comic book form because that’s what you loved as a kid—you may be limiting your reach, and missing potential new buyers who read everything on their phones, and very little on paper. But… maybe you can reach those people and bring them into bookstores, and comics shops with free digital promotional material on YouTube? An animatic based on your comic?

Can you make a movie and sell copies as downloads? Does a comic have to be printed by Marvel, or formatted like a WebToon to get copies to readers? Is there a way to sell your novel as a PDF? Can you sell your first film online, ad-free, then put advertisements in free downloads to make revenue, and reach farther and wider? Can you make a ‘how-to’ video of how you put together your creation to encourage others and get attention, while also promoting your work?

Look at things differently. Look at things realistically. See your options. ALL your options. Then make what you love. What you’re passionate about. What gets you up in the morning, and keeps you going into the wee hours of the night, knowing exactly who and what your unique market is, and how best to reach them.

Become your own Gatekeeper. It may not be obvious, yet, but you already have the keys.

But what do I know? Nobody really knows anything.

Really enjoying your blog/comments/editorials... Whatever the kids call them nowadays. Thank you, Chuck.